Easter Vigil, also called the Paschal Vigil or the Great Vigil of Easter, is a liturgy held in traditional Christian churches as the faithful wait to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Great Vigil is held in the hours of darkness between sunset on Holy Saturday and sunrise on Easter Day and is considered to be the first celebration of Easter.

Easter Vigil, also called the Paschal Vigil or the Great Vigil of Easter, is a liturgy held in traditional Christian churches as the faithful wait to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Great Vigil is held in the hours of darkness between sunset on Holy Saturday and sunrise on Easter Day and is considered to be the first celebration of Easter.

For the past decades, I have contributed creative re-interpretations of the classic texts at Easter Vigil services at various churches. In 2010, I contributed a musical re-telling of the Daniel story: Well of Promise. In 2022, I created River of Words, a re-telling of the Exodus Story of Passover, with animation by Jack Zierhut .

Moses stuttered. He was inarticulate. The tongue clove to the roof of his mouth, He was hopeless with language, his words always meant nothing, and even when he did utter words, they stumbled and tripped and broke apart. The stuttering fool, Aaron called him.

Yet despite his long disability, Moses found a way to give Pharaoh words. Words of warning. Words of power. Words from God.

But the Pharaoh chose to discard those words, or misunderstand those words, or mis-interpret those words, or merely to think Moses was lying.

That’s the problem with language. It’s so easily twisted around. So easily found to be wanting in expressing what is real, what our hearts really need to hear. Fake News, we cry, when we don’t want to hear something hard, something painful, something true.

And so the Pharaoh in his arrogant act of closing his ears, was visited by an angel. The angel did not pass over his house. The angel came, the angel stayed, the angel sat on his child’s chest until his child’s lungs failed. The angel took his child’s breath, ounce by ounce, until all air was gone, and his child’s life was snuffed out.

Pharaoh woke to a dead son, and a grieving nation. He woke to pain, and suffering and death. These are things that can’t be fully captured in words, can’t be sewed up in convenient envelopes of language, they are too deep, too hard, too much for words to hold. Words break open under such pressure, words are inadequate to real grief.

There was nothing that could be said, nothing to redeem Pharaoh’s child’s life. The angel was gone, could no longer be bargained with. So the Pharaoh, wordless, struck dumb, sent the Israelites out of his kingdom.

They fled, following Mose’s words.

They came to the shore of a vast horizon of water. They came to what is commonly called the Red Sea, but in Hebrew is known as Yam Suph, the Sea of Reeds.

You might remember that these same reeds were used – are still used – by Egyptians to make the first paper, papyrus.

The Sea of Reeds… the sea that made papyrus. In fact, this very sea of reeds is the place where white pith is extracted from the triangular stalk of the reed plant that grows in freshwater in northern Egypt. This is the very place where all ancient texts were first birthed. This sea is the birthplace of language.

Imagine this intrepid group of travelers stalking out of the sand and confronting white paper vast as the ocean criss-crossed with symbols, echoing with language. How would you cross that terrible terrain of cryptograms etched into the ancient sky?

They confronted, right then and there, that terrible dichotomy brought about at the Tower of Babel, when human language was confused, and all became chaotic, because we still can’t understand one another. When the Israelites halted here, they were halted, as we all are, by that great barrier between us made of words, the colossal error-prone, misinterpreted sea of language itself.

Today, we float in the same water, we live in a world of chaos constructed of language –Fake News, gaslighting, mansplaining, emoticons, mis-translation and all the violence done to others because of words that mean God and Love Embodied – Allah and Christ.

Here are what Human Beings are like: We weave a web of words like a spider and live in it, and call it world. Today, we are confronted by a vast abyss of words that create division, that destroys our ability to move forward, to find sustenance and to enjoy all that God has given us. We are blocked by a River of Words, a Sea of Destructive Language, a Bottomless Abyss of Misunderstanding.

Moses knew the future. Now the words caught again in Moses’s mouth when he saw the barrier that held them back. He stuttered, he pondered. He knew the future. We know the future.

Moses will stamp his staff and his staff will break.

People will drown in the Red Sea. The survivors will be enslaved again.

People will die because of a sea of lies from the White House.

A baby will be killed by Herod’s purge. No savior will come.

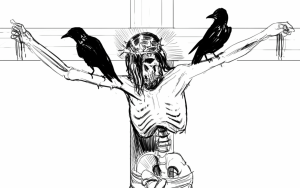

A man die on a cross and worms eat his flesh. No resurrection.

Yet despite all the weight of language that held Moses back, despite the entire absence of any bridge to the other side, Moses stamped his staff, he closed his eyes and sang the song of invocation, the qara Besem Yahweh.

Why did he do this? What rose in his heart beyond reason, beyond logic, beyond words? Something rose in him, something that spoke to our deep human longing. Something that said that we are more than this weak vehicle of stumbling stuttering language.

Hope.

Always there is hope.

Even when words hold us back, understanding limits us, powers of logic make us inarticulate and weak. Even then, there is still hope. The words that describe our reality – one of death, one of paranoia, one of destruction – that’s not the whole world. It’s not all there is.

There is always hope.

And there is always love.

And in this story, at the Sea of Reeds, where language was first birthed, confronted by that vast white spectacle, a Sea of Babelous Confusion of Words and Language, a destructive ocean of endless online content, at that moment, there was something that broke a crack in language itself.

Parable.

See, the deep parables of the bible confront our expectations and soften our hearts to hear a deeper truth. As the theologian John Dominic Crossan writes in his little book THE DARK INTERVAL, the Christ story breaks open our expectations, destroys our preconceptions, and the parables of Christ pre-figure the breakdown in our expectations and our understandings.

The cracks and rifts in the parable of the Bible confront our very understanding of reality. Things don’t happen in language that happen in our hearts.

Could a lost people find a home? Could people walk on dry land through an ocean? Could a virgin give birth? Could a man rise from the grave?

Could we live in harmony, in love, in peace and justice?

I cannot use language to capture this hope.

In the beginning was the Word…

History of Easter Vigil

The original twelve Old Testament readings for the Easter Vigil survive in an ancient manuscript belonging to the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem. The Armenian Easter Vigil also preserves what is believed to be the original length of the traditional gospel reading of the Easter Vigil, i.e., from the Last Supper account to the end of the Gospel according to Matthew. In the earliest Jerusalem usage the vigil began with Psalm 117 [118] sung with the response, “This is the day which the Lord has made.” Then followed twelve Old Testament readings, all but the last being followed by a prayer with kneeling.

(1) Genesis 1:1–3:24 (the story of creation); (2) Genesis 22:1-18 (the binding of Isaac); (3) Exodus 12:1-24 (the Passover charter narrative); (4) Jonah 1:1–4:11 (the story of Jonah); (5) Exodus 14:24–15:21 (crossing of the Red Sea); (6) Isaiah 60:1-13 (the promise to Jerusalem); (7) Job 38:2-28 (the Lord’s answer to Job); (8) 2 Kings 2:1-22 (the assumption of Elijah); (9) Jeremiah 31:31-34 (the New Covenant); (10) Joshua 1:1-9 (entry into the Promised Land); (11) Ezekiel 37:1-14 (the valley of dry bones); (12) Daniel 3:1-29 (the story of the three youths).