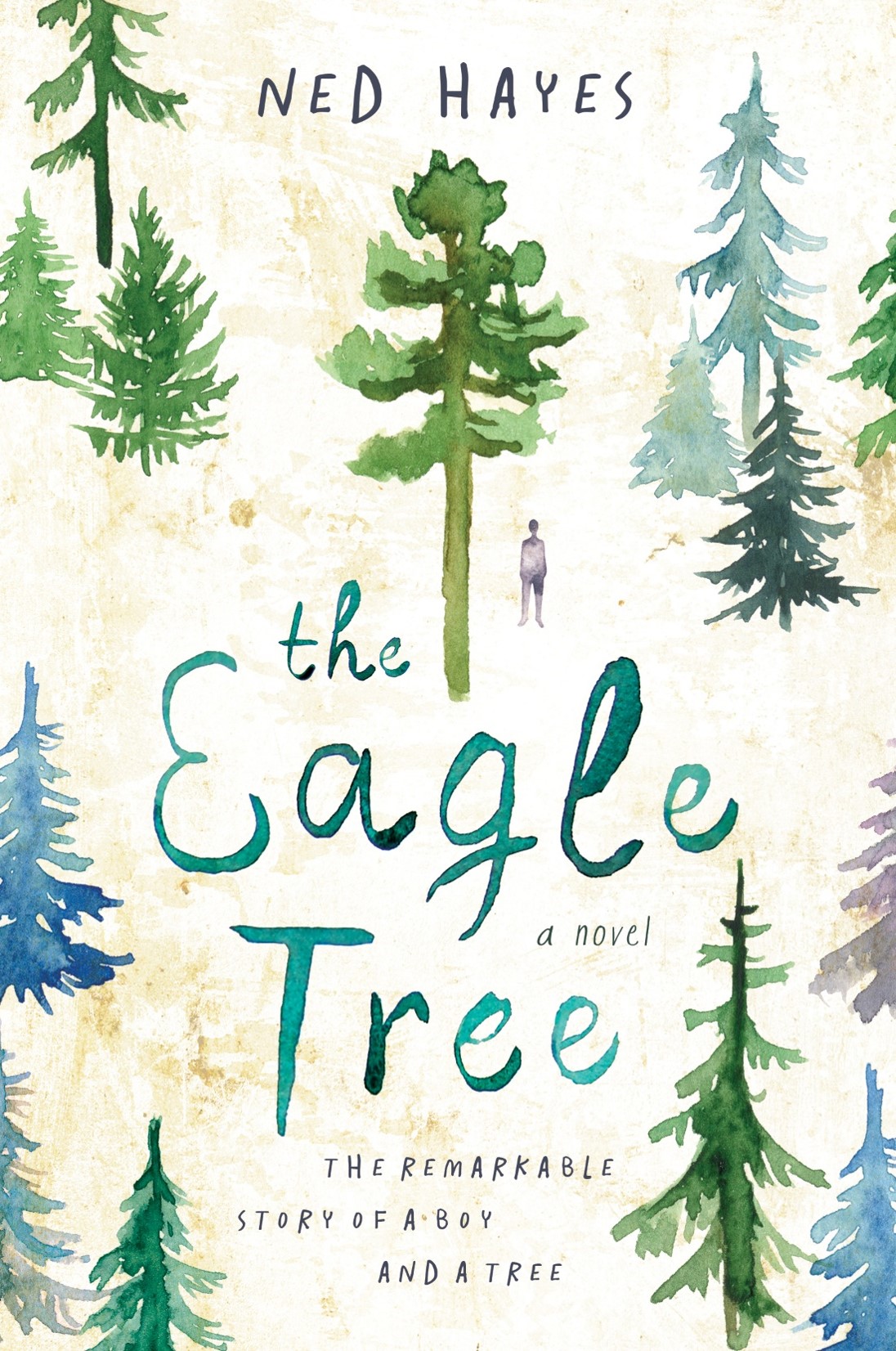

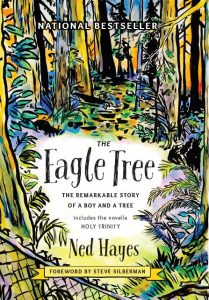

A new commemorative limited hardcover edition of the bestselling novel The Eagle Tree by Ned Hayes has just been published. The new edition has a spectacular cover by Pacific Northwest author and artist Hal Schrieve, which was selected for the National Book Award Long List for Young People’s Literature.

A new commemorative limited hardcover edition of the bestselling novel The Eagle Tree by Ned Hayes has just been published. The new edition has a spectacular cover by Pacific Northwest author and artist Hal Schrieve, which was selected for the National Book Award Long List for Young People’s Literature.

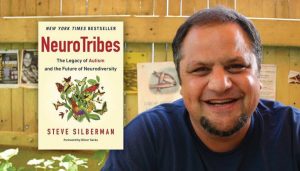

I’m also excited to announce that Steve Silberman, a friend of Oliver Sacks, winner of the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction, and author of the New York Times bestselling history of autism Neurotribes, has written a lovely heartfelt foreword for the new hardcover commemorative edition of The Eagle Tree.

Here’s the complete foreword by Steve Silberman.

FOREWORD

It is the special, magical quality of some precious books that they seem to contain the whole universe in miniature. Ned Hayes’s The Eagle Tree is such a book. By fully inhabiting the subjective experience of his narrator—Peter March Wong, an insatiably curious autistic teenager in Washington State with an unruly passion for climbing trees—Hayes brings vast worlds into focus, from the intricate web of interspecies relationships that is the foundation of the ecology of the Pacific Northwest to the confusing network of interpersonal relationships that March must learn to navigate as he comes of age. Accompanying him on his thrilling and perilous journey toward independence, we not only learn much about the majestic arboreal presences whose “true names” he repeats like a holy litany, we discover that diversity in communities of human minds is as valuable as diversity in communities of living things.

Creating a credible, complexly human disabled narrator can be tricky for a nondisabled author, but Hayes’s years of mentoring and listening to students on the spectrum as a teacher have served him well. He brings us along on March’s atypical hero’s journey without resorting to the usual pity-evoking clichés that afflict most writing about disabled people in general and about people on the autism spectrum in particular.

March is not presented as a hapless, bumbling, trivia-obsessed Aspie who tramples social norms to comedic effect; nor is he caricatured as a saintly savant who exists primarily to solve the problems of nondisabled characters. Instead, Hayes presents March as very much his own person, avidly pursuing his quest to acquire knowledge about the trees he loves, even in the face of obstacles introduced by adults who feel confident that they’re acting with his best interests in mind. Rather than framing March as the unreliable narrator of his own story, Hayes probes the ways that March’s unusual mind enables him to be an exceptionally reliable narrator of aspects of experience that most “normal” people miss.

Furthermore, it is only in the past couple of decades that the autism diagnosis has become available to teenagers and adults, and thus only recently that autobiographical accounts of lives on the spectrum have become available to readers. In addition to listening to his students, Hayes has clearly absorbed the work of autistic writers like industrial designer Temple Grandin, which enables him to illuminate his narrator’s thought processes from the inside with the intimacy and veracity of lived experience.

But March is more than an embodiment of his disability, and there’s more at stake in The Eagle Tree than the coming-of-age of a single young man. The overarching context of his journey is the tenuous fate of the imperiled ecosystem in which he finds himself. March’s identification with trees—particularly with the regal Ponderosa pine that becomes the primary focus of his tree-climbing desire and gives the book its title—is so all-consuming that he comes to resemble a teenage Walt Whitman, seeking communion with the magnificent ancient beings that tower over his landscape. In Whitman’s era, however, there was no reason to believe that the resilient natural world that the good gray poet praised in poems like “This Compost” would fail to thrive into the far future. By contrast, in our own time, the old-growth forests that once blanketed the Pacific Northwest have been nearly erased from the map. Nearly inadvertently, March’s love of trees leads him to become their champion at a moment when they most need one.

In some First Nations societies, people with cognitive differences were accorded special status as shamans who acted as interlocutors between the living and the dead, or between the realm of humans and the realm of animals. One reason that Hayes’s tale resonates with uncanny familiarity is that it taps into archetypal springs of meaning in old-growth layers of consciousness—the substrate of fairy tales and dreams. At the same time, March’s quest to learn as much as he can about the trees he loves leads him deep into the study of the science of living systems. While people like him are often described by clinicians as having “limited” or “obsessive” interests, March’s intense focus on a single tree becomes a lens through which the machinery that sustains the whole planet becomes visible.

In some First Nations societies, people with cognitive differences were accorded special status as shamans who acted as interlocutors between the living and the dead, or between the realm of humans and the realm of animals. One reason that Hayes’s tale resonates with uncanny familiarity is that it taps into archetypal springs of meaning in old-growth layers of consciousness—the substrate of fairy tales and dreams. At the same time, March’s quest to learn as much as he can about the trees he loves leads him deep into the study of the science of living systems. While people like him are often described by clinicians as having “limited” or “obsessive” interests, March’s intense focus on a single tree becomes a lens through which the machinery that sustains the whole planet becomes visible.

“I would like to think the trees and I have something in common,” March says to himself near the end of this enchanting book. Perhaps a better word than independence for what he achieves in the course of his journey is interdependence: the knowledge that every living being is connected to every other living being through an intricate web of relationships that are often hidden from the casual observer. It is one of the marvelous paradoxes of the human condition that we often discover who we are only by loving someone else. By giving the Eagle Tree his full attention, March glimpses his place in the order of all things.

National bestseller, named in 2016 as one of the Top 5 Books on the Autistic experience.

Buy THE EAGLE TREE at indie bookstores, Amazon and Barnes & Noble.